NOTE: Unless stated, all photographs are supplied by Arthur Coopes.

Arthur George Shelley (1841-1925)

and Mary Clarissa Shelley (nee Walker) (1849-1912)

This is the story of the Shelley family, from their time in Kerang, Victoria, through their move to Western Australia during the 1890s t0 the WA Goldfields and the earlier times of their lives in WA. Arthur Henry Coopes, great-grandson of Arthur George and Mary Clarissa Shelley, kindly shared his family story with us back in 2005. This is an excerpt of the family story which he wrote to supplement the book, “The Shelley Family”, compiled by Jean Stewart of “Kenmore Park”, Kenmore, Queensland.

Background: For those not familiar with the story of the Shelleys in Australia, I shall briefly outline their early history. It may help set the scene for the story that follows.

The Reverend William Shelley left England in 1798 to work for the London Missionary Society as an artisan missionary in the islands of the South Pacific Ocean. After many adventures, he moved to the colony of New South Wales, married Elizabeth Bean and the couple settled in Parramatta around 1806. They had seven children of whom six lived to mature years. Three sons, William, George and Rowland, were involved in exploration and land settlement in south-eastern NSW and north-eastern Victoria, in particular in the Tumut area and along the upper Murray River. The three daughters, Lucy, Elizabeth and Mary, married into well-known and influential families of the early NSW colony, and the stories of those families form a large part of the history of the larger Shelley family too. Jean Stewart’s book covers all of the above stories thoroughly.

The “Western Australia” Shelley family line descends from Rowland Shelly and his first wife, Maria Brillia Louisa PETERS who had eleven children, Emmeline, John Darlford, Arthur George (the “western” forbear), Alice Elizabeth Mary, Jane Draper, Kathleen, Susannah Maria, Elizabeth (died as an infant), Benjamin, Lucy and Robert (also died as an infant). Rowland spent much of his life on properties along the central/upper Murray River in NSW and Victoria. After Maria died in 1877, Rowland married the much younger Julia TALL. They lived in Sydney, where Rowland died in 1888, and had three more children. During the latter years of his life, he appears to have corresponded frequently with his son Arthur George, who was to be the executor of his will.

The ages of the fourteen children fathered by Rowland spanned 48 years!

The “Western” Shelleys – Origins

We have little “hard” information about Arthur George Shelley before he came to Kerang, Victoria, around 1870. It is possible that he had some association with the Patchell family, who settled in Kerang in 1857 and went on to become very influential citizens of the district for many decades to come. They would have come to Kerang around the same time that Rowland Shelley and his family were living relatively nearby in northern-central Victoria. A son of that family, Woodford John Williams PATCHELL was subsequently to become Arthur George’s brother-in-law, by marriage.

A better starting point is Parker Newton WALKER, about whose origins we have far more information. Parker Newton Walker was a wool merchant who emigrated from Huddersfield, Yorkshire, to Victoria on the ship “Serampore” in July 1852. He was accompanied by his second wife, Clarissa (nee Baggaly), their four children (Herbert Osborne, Bernard Oswald, Mary Clarissa and Hilda Maria Harding Walker), and the two children of his first wife, Mary Ann (nee Robinson), Percy Nicholson and Theresa Stuart Walker. Parker Newton Walker kept a detailed diary of his family’s journey from England to Melbourne, which is now in the care of Geoff Griffiths, grandson of Arthur George’s daughter, Maude.

Shortly after he arrived in Melbourne in October 1852 and after finding living conditions there at the time to be very poor, Parker Newton Walker and his family moved on to Launceston, Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), in November 1852. He went into a business partnership that was formally terminated in July 1853, after which he returned to Melbourne. His registered occupation in 1856 to 1862 was as a woolbroker in Melbourne, and he appears to have lived in its inner suburbs until his death in April 1864. Parker’s second daughter, Mary Clarissa, married Arthur George Shelley on 3 December 1872.

Arthur George and Mary Clarissa Shelley in Kerang, Victoria

Shortly after their marriage, Arthur George and Mary Clarissa undertook the first of two significant instances of caring for the orphaned children of other family members. They undertook the care of Ann Patchell, the 2-year-old daughter of James Maillard Patchell, a brother of Mary’s brother-in-law, Woodford Patchell, after James’ wife, Ellen, had died during the birth of her next child, Ellen Theresa (Nellie). Arthur and Mary’s first daughter, Hilda, was born a few months later. Ann was three years older, almost to the day, than Hilda and became, therefore, virtually a ‘big sister’ to Hilda and subsequently to the other Shelley children.

Arthur George and Mary Clarissa first lived in Kerang near the Patchell home. Their own permanent home, “Riverside”, on the banks of the Loddon River that flows through Kerang, was built by them in about 1885. Today, it is now Kerang’s Historical Museum.

Mary Clarissa’s (half) sister, Theresa, died quite young (in 1879), and Mary Clarissa and Arthur George, in the second instance of caring, subsequently accepted a lot of the responsibility for the family of the widowed father. I understand that the eight Patchell and five Shelley children grew up virtually as brothers and sisters at “Riverside”.

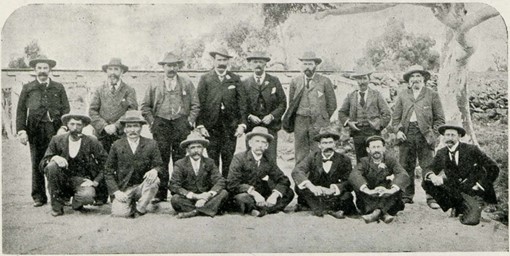

Little more than the above is known about the Arthur George & Mary Clarissa Shelley’s family’s life in Kerang. Arthur George was a lieutenant in the Victorian Mounted Rifles. Mary Clarissa taught music and was the organist for the Roman Catholic Church for a time.

The Family’s move to the Western Australian Goldfields

Arthur George moved to WA around 1894 – 1895 with a Mr Robert Crawford, a baker from Victoria. He left Mary Clarissa and the children behind in Kerang. At Fremantle, they bought a dray and two draught horses and travelled to Coolgardie. From there, they proceeded north from Coolgardie. Mr Crawford had a strike about 50 miles away that was to become the (very rich) Carbine Mine.

Arthur George settled at “the 25-mile camp”, so called because it was 25 miles from Coolgardie. It was also known to him and his family as Speakman’s Find, and he remained there and operated a store/post office, apparently for several years.